The History of Brownhelm Township

Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Settlement

Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Settlement

The Early Settlers of Brownhelm Township Ohio

Col. (Judge) Henry Brown

William Alverson

- Emily Louisa- born April 30, 1820 in Brownhelm, Ohio; died September 2, 1882 in Lee, Massachusetts

- Mary Lucinia - born September 24, 1821; died April 18, 1840 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts

- Daniel Fairchild - born February 19, 1823; died December 5, 1893 in Canandaigun, New York (On June 15, 1848 Daniel Fairchild Alverson married Sarah Cowdery (1822-1906) in Rochester, Monroe Co., New York. Sarah was the daughter of the celebrated frontier printer and editor, Benjamin Franklin Cowdery (1790-1867).)

- Elizabeth Elvira - born February 8, 1825; died April 1895 in Brownhelm, Ohio

- Frederick William - born December 14, 1829; died August 1894 in Canadaigun, New York

- Julia Harriet - born March 17, 1834, Stockbridge, Massachusetts; died March 8, 1861 in Lee, Massachusetts

Grandison Fairchild

Deacon Shepard

Stephen James

Orrin Sage

Bacon

Enos Cooley

Elisha Peck

Deacon George Wells

John Graham

Abishai Morse

Ira Wood & Stephen Goodrich

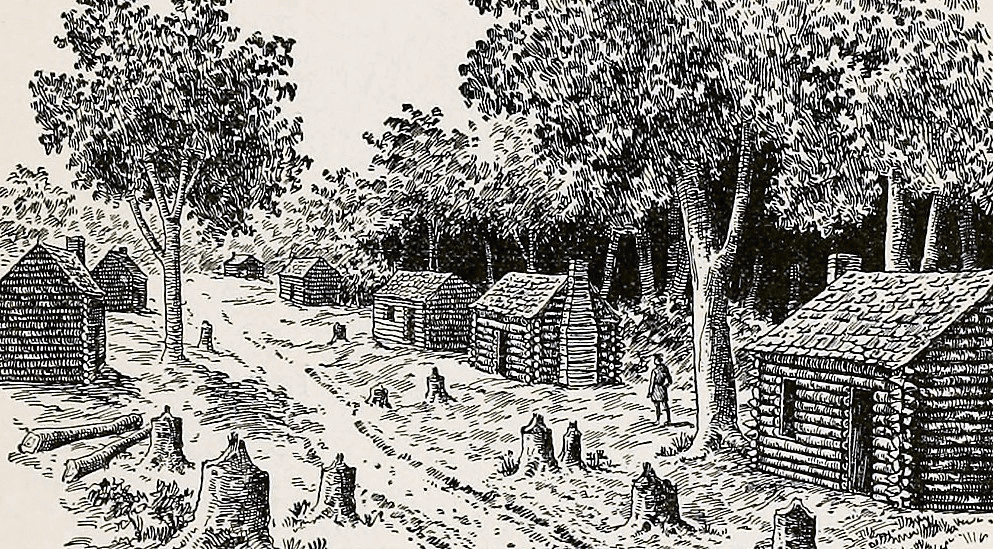

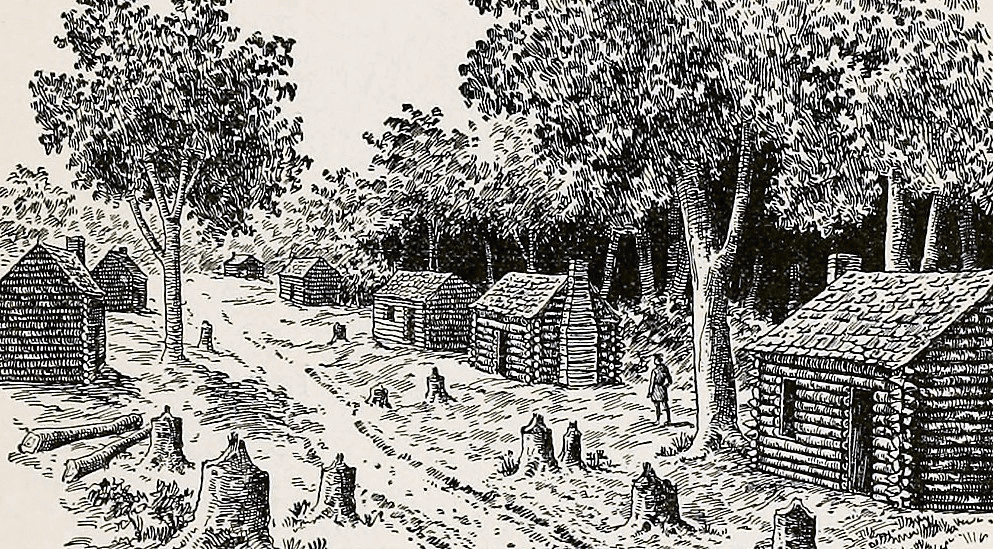

Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio

The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm

Clothes & Shoes

Food

Black Salts

Wild Animals

One of the features of early life here was familiarity with the wild animals that had possession of the country. The howl of the wolf at night was as familiar as the whip-poor-will’s song - not the small prairie wolf so well known at the west, but the powerful wolf of the forest, the black and the gray. They passed in droves by the dwellings at night, sometimes when the new comers had only a blanket suspended in the opening for the door. Sometimes they crowded upon the footsteps of a belated settler, passing from one part of the settlement to another, The boy crossing the pasture on a winter morning would often see the blind track of a wolf that had loped across the night before. If he had forgotten to bring in his sheep at evening, he might find them scattered and torn in the morning. A dog that ventured from the house at night, sometimes came in with wounds more honorable than comfortable. The wolf was a shy animal, seldom showing itself by day light.

Probably not one in a dozen of the early inhabitants ever saw a wolf in the forest; yet these animals roamed the woods around Brownhelm for years. Mr. Solomon Whittlesey once snatched his calf from the jaws of a wolf, at night, with many pairs of hungry eyes gleaming upon him through the darkness. In 1827, the county commissioners offered a bounty for wolf scalps - three dollars for a full-grown wolf, and half the sum for a whelp of three months. Whether any drafts were ever made upon the treasury does not appear.

Now and then a wolf was taken in a trap or shot by a hunter. Probably less than a half-dozen were ever killed in the township. About the winter of 1827-28, wolf hunts were organized in the region on a grand scale, conducted by surrounding it tract of country several miles in extent, with a line of men within sight of each other at the start, and approaching each other as they moved toward the center. The first of these hunts centered in Henrietta, and resulted in bagging large quantities of game, but never a wolf. A single wolf made his appearance at the center, and was snapped at and shot at by many a rifle, but he got off with a whole skin.

The sport involved danger from the cross-shooting as the line drew near the center, and Park Harris, of Amherst, mounted on a horse, received a shot in the ankle. To avoid this danger, the next hunt centered on the river hollow, about the mill in Brownhelm, but the scale on which it was arranged was too grand to be carried out. The lilies were too extended and broke in many places, resulting in gathering upon the flat a small herd of deer and a solitary fox, barely furnishing an occasion for the hundreds of huntsmen above to discharge their pieces, as the frightened animals escaped into the woods up the river. It was an utterly fruitless chase. A more exciting chase was the slave-hunt of a later day, in which the people bewildered and foiled the kidnappers.

Bears were less numerous than wolves, but they were perhaps more often seen. One was shot by Solomon Whittlesey, from the ridge, a little east of the burying ground. One of the trials of childish courage was to pass the tree against which tradition said that he rested his rifle in the shot. Another dangerous tree was the large basswood that leaned over the brook, a little to the south-east of Harvey Perry’s orchard. Mrs. Fairchild, going over the ridge to bring a pail of water from the spring, once drove a large black animal before her which she thought a dog until he scrambled up that tree when she returned home without the water. The tree stood close by the track that led to Mr. Peck’s, and it was a test of pluck for a child to pass that tree just as the evening began to darken. One day, one of a half dozen sheep was missing. In looking for the lost animal, a place was found where it seemed to have been dragged over the fence where a bear had made his feast, leaving the wool scattered about and a few large bones. The tracks were still fresh in the mud.

Such occurrences gave a smack of adventure to child life in the new country, and it was a matter of every day consultation among the boys, what were the habits of the various animals supposed to be dangerous, such as the wolf, the bear, the wild cat, and the panther, and by what tactics it was safest to meet them. Similar discussions were had in reference to the Indians, who had required a bad reputation during the war, then recent, with England. The prevailing opinion was, that any fear exhibited towards an Indian, or a wild beast, put one at a great disadvantage.

Deer were far more plenty than cattle, and the sight of them was an everyday occurrence. A good marks man would sometimes shoot one from his door. The same was true of wild turkeys. Raccoons worked mischief in the unripe corn, and a favorite sport of the boys was “coon hunting” at night, the time when the creature visited the corn. A dog traversed the cornfield to start the game, and the boys ran at the first bark of the dog, to be in at the death. When the animal took to a tree, it was cut down, or a fire was built and a guard set to keep him until morning, when he was brought down by a shot. The motive for the hunt was three-fold - the sport, the protection of the corn, and the value of the skin; the raccoon being a furred animal.

The greatest speculation in this line of which the town can boast, was made by Job Smith, “a man of some note.” He is said to have bought a quantity of goods of a New York dealer, promising to pay “five hundred coon skins taken as they run,” naturally meaning an average lot. The dealer, after waiting a reasonable time for his fur, came on to investigate, and inquired of his debtor when the skins would be delivered. “Why,” said Mr. Smith, “you were to take them as they run; the woods are full of them; take them when you please.” The moral of the story would not be complete with out stating that the same Job Smith was afterwards arrested as a manufacturer of counterfeit coin.

Thrifty men pursued the business of hunting as a pastime. The only man in town, perhaps, to whom it afforded profitable business, in any sense, was Solomon Whittlesey. Other professional hunters were shiftless men, to whom hunting was a mere passion, having something of the attractions of gambling. Mr. Whittlesey did not neglect his farm, but he knew every haunt and path of the deer and the turkey, and was often on their track by day and by night. He reported the killing of one bear, two wolves, twenty wild cats, about one hundred fifty deer, and smaller game too numerous to specify. One branch of his business was bee hunting, a pursuit which required a keen eye, good judgment and practice. The method of the hunt was to raise an odor in the forest, by placing honey comb on a hot stone, and in the vicinity another piece of comb charged with honey. The bees were attracted by the smell, and having gorged themselves with the honey, they took a bee-line for their tree. This line the hunter observed and marked by two or more trees in range. He then took another station, not on this line, and went through the same operation. Those two lines, if fortunately selected, would converge upon the bee tree, and could be followed out by a pocket compass. The tree, when found, was marked by the hunter with his initials, and could be cut down at the proper time.

Another form of the sport of hunting was even more classic, the hunting of the wild boar. For many years there was an unbroken forest, two miles in breadth, running through the township, between the North Ridge and the lake shore farms. This forest became the haunt of fugitive hogs that fed on the abundant mast, or, in Yankee phrase, “shack,” which the forest yielded. These animals were bred in the forest, and in the third generation became as fierce as the wild boar of the European forest. The animal in this condition was about as worthless, for domestic purposes, as a wolf, as gaunt and as savage. Still it was customary, in the fall and early winter, to organize hunts for reclaiming some valuable animal that had become thus degenerate. The hunt was exciting and dangerous. The genuine wild boar, exasperated by dogs, was the most terrible creature in the forest. His onset was too sudden and headlong to be avoided or turned aside, and the snap of his tusks, as he sharpened them in his fury, was somewhat terrible. Two at least of the young men, Walter Crocker and Truman Tryon, were thrown down and badly rent in such encounters, and others had narrow escapes.

The principal fishing ground of the early years was the “flood wood” of the Vermillion. The lake fishing is a modern discovery. It was not known that the lake contained fish that were accessible. Other sports and recreations were few and simple, most of them presenting the utilitarian element. There were logging bees to help a man who had been sick or unfortunate, raisings to put up a log cabin or barn, and militia trainings, which were entered into earnestly by men who had smelt powder in the recent war.

Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Settlement

Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Settlement